Constructive Notes ®

Introduction

An insurer bears the onus in establishing that a particular claim falls within an exclusion clause (Pye v Metropolitan Coal Co Ltd (1934) 50 CLR 614, 625).

In relation to exclusions of damage caused by flood, as was observed by His Honour Jackson J in LMT Surgical ([2014] 2Qd R 118 at [21]) the scope of the cover or exclusion of damage caused by flood, depends on the specific language deployed in the particular policy on the subject matter and is not determined by cases decided upon the meaning of other clauses in policies which deploy other language or by broad statements as to purpose or object.

Up until 11 October 2021, the two most recent Australian decisions on the operation of an exclusion for ‘flood’ were the Queensland Supreme Court decisions in LMT Surgical and Wiesac & Anor v Insurance Australia Group Limited [2018] QSC 123.

The first of those cases concerned the words ‘water overflowing from the normal confines’, and the second ‘water escaping or released from the normal confines’.

The insurer was unsuccessful in the first mentioned case, but was successful in Wiesac, with the Judge noting that there was only one word which was different in the flood exclusion in that case compared to that considered in LMT Surgical.

On 11 October 2021, Dalton J delivered judgement in the Queensland Supreme Court in Landel Pty Ltd & Anor v Insurance Australia Ltd [2021] QSC 247.

As part of that case, Her Honour was called upon to consider an exclusion for ‘flood’ which was in all respects identical to the exclusion the subject of the Court’s judgement in LMT Surgical. On this occasion however, the Court upheld the operation of the exclusion, noting that it was clear that the decision in LMT Surgical did not purport to lay down any general rule.

Landel – ‘Water Overflowing from the Normal Confines’

Facts

The background facts giving rise to the claim as relevant to the operation of the exclusion for ‘flood’ were set out in the following paragraphs of the judgement:

[1] The plaintiffs owned land in Townsville which was the site of a shopping centre. The defendant insured the plaintiffs under an industrial special risks policy. There was monsoonal rain and consequent flooding in Townsville in late January and early February 2019.

[2] Between 6:20pm on 3 February 2019, and about 12:20am on 4 February 2019, water flowing over the ground entered the shopping centre and rose to the height of around half a metre.

[3] The insurer accepted a limited liability for the flooding damage on 3 and 4 February 2019; it stated that its liability was limited to $250,000 because the losses were caused by flood as defined.

[4] The plaintiffs sued claiming indemnity under the policy contending that the physical circumstances of the inundation were not within the definition of flood in the policy, and that therefore the $250,000 limit on the insurer’s liability was inapplicable.

Terms of the Policy

[14] The policy provided that, ‘In the event of any physical loss, destruction or damage … not otherwise excluded happening at the Situation to the Property Insured … the Insurer will, subject to the provisions of this Policy including the limitation on the Insurer’s liability, indemnify the Insured in accordance with the applicable Basis of Settlement’.

[15] There was also consequential loss insurance. The insurer promised that ‘In the event of any building or any other property or part thereof used by the Insured at the Premises for the purpose of the Business being physically lost, destroyed or damaged by any cause or event not hereinafter exclude … and the Business carried on by the Insured being in consequence thereof interrupted or interfered with, the Insurer will, subject to the provisions of this Policy including the limitation on the Insurer’s liability, pay to the Insured the amount of loss resulting from such interruption or interference in accordance with the applicable Basis of Settlement’.

[16] The placement slip accepted by the insurer added ‘perils exclusions’ to the policy. They included:

‘3. physical loss, destruction or damage occasioned by or happening through:-

(a) flood, which shall mean the inundation of normally dry land by water overflowing from the normal confines of any natural watercourse or lake (whether or not altered or modified), reservoir, canal or dam.’

[17] Although this clause was worded as an exclusion, it was accepted that, having regard to the documents which comprised the policy, in fact it operated to define flood for the purpose of the policy, and that the policy operated to limit the insurer’s liability for flood to $250,000, rather than exclude it altogether. It was also accepted that clause 3(a) had to be treated as an exclusion in construing the clauses in the policy which contained the insurer’s promise of indemnity.

Expert evidence

The cause of the inundation of the shopping centre on 3 and 4 February 2019 was the subject of expert evidence which occupied almost all of the trial time.

The judge found [at 37] that there was a vast gulf in the quality of expert opinion in the case between the plaintiff’s expert on the one hand, and the defendants’ experts on the other and had a strong preference for the opinions of the defendants’ experts over those of the plaintiff’s expert.

Uncontroversial Background to Inundation of 3 and 4 February 2019

[38] The shopping centre was located in the middle of what was once the floodplain of Gordon Creek. In 2014/2015 the Townsville City Council commissioned a flood study of the area and, acting on the study, undertook earthworks to divert the flow of Gordon Creek to the north of its original course. After that, it allowed the shopping centre (and quite a number of houses) to be built on the old floodplain.

[42] There had been days of monsoonal rain before 3 February 2019. From about 4.00 pm on 3 February there were two rainfall events after which water entered the shopping centre. Storm Burst 1 began at about 4.00 pm after a period of about six hours during which no rain fell. Storm Burst 1 lasted 130 minutes and was followed immediately by Storm Burst 2 which lasted 140 minutes. During each of Storm Burst 1 and Storm Burst 2 around 70 millimetres of rain fell.

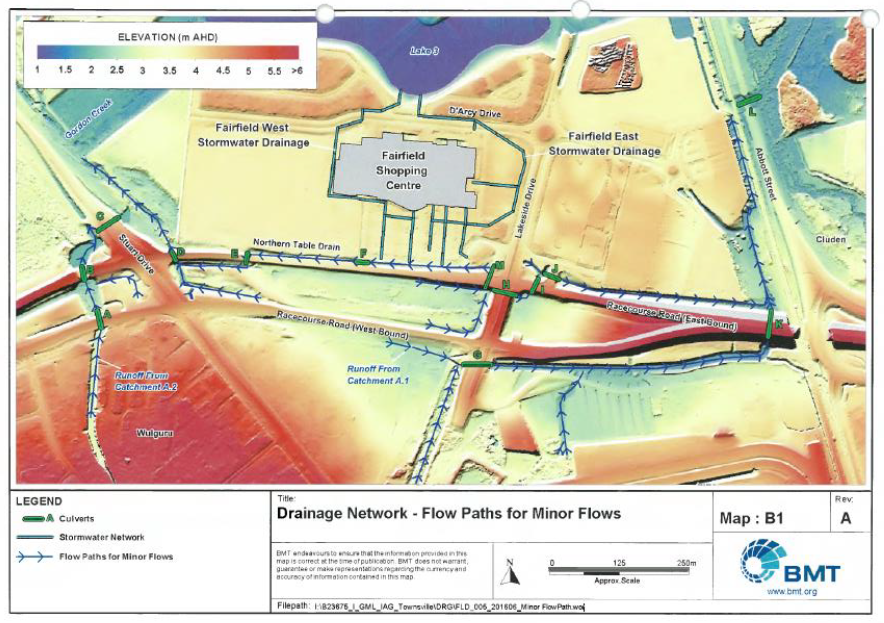

[43] No expert was of the view that inundation of the shopping centre was caused by rain falling over the immediate environs of the centre. It was common ground that the inundation was caused by the flow of water into the centre from some other area.In the judgement, there were three reproduced images from the experts to assist in understanding the matters which fell for decision in the case. One of these, provided by one of the defendant’s experts appears below.

In the judgement, there were three reproduced images from the experts to assist in understanding the matters which fell for decision in the case. One of these, provided by one of the defendant’s experts appears below.

Area of Expert Controversy

[44] In broad terms the difference between the experts was that the plaintiff’s expert swore he believed that as the result of Storm Bursts 1 and 2, runoff from Catchment A1 on Mt Stuart travelled north across both carriageways of Racecourse Road, across the table drain and into the shopping centre causing the inundation. A later variation of this might have been that this runoff travelled at least to the table drain, where it mixed with the water already in the table drain and caused this mixture of water to inundate the shopping centre. The defendants’ experts were of the view that water inundating the centre came from overflows from the Ross River and Gordon Creek which formed a large sheet of water travelling west across the floodplain on which the shopping centre was located.

Conclusion as to the plaintiff's expert evidence

Dalton J stated [at 114] that she would not rely upon the plaintiff’s expert’s views in deciding issues which were relevant to the case unless they were adopted or agreed by the defendant’s experts. Her Honour also rejected his views so far as they were based on the modelling evidence. Her Honour put the plaintiff’s expert’s opinions to one side and turned to whether or not the defendant had proved by their expert evidence a basis upon which the flood exclusion applied: Dalton J made clear that the case was not to be resolved on a competition between expert reports so that the plaintiff automatically failed because she rejected the plaintiff’s experts’ views. Her Honour noted that it was the insurer who bore the legal and evidentiary onus of proving that the exclusion applied: Wallaby Grip Ltd v QBE Insurance (Australia) Ltd; Stewart v QBE Insurance (Australia) Ltd (2010) 240 CLR 444 [25].

Conclusions as to the Modelling

Her Honour accepted [at 162] that although modelling had its limitations and was, in effect, a secondary source of scientific proof, the modelling performed by the defendants’ experts was of assistance in understanding the inundation of the shopping centre. Even if allowance was made in the model for all of the plaintiff’s expert’s many criticisms, it still showed that water did not cross Racecourse Road from south to north and that the vast majority of water which inundated the shopping centre came from Drain A2, Gordon Creek and the Gordon Creek diversion.

Conclusions as to Cause of Inundation

Dalton J [at 163] was more than satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the insurer had proved the cause of the inundation in accordance with their experts’ evidence, finding that their evidence was convincing because it was based on the real physical parameters of the site and the rainfall events. It was consistent with the photographs and footage both before and after the flood. It is consistent with more theoretical evidence, such as the plaintiff’s expert’s schematic diagrams and modelling. It was consistent with the water levels and rates of rise at the Gordon Creek Alert.

Further Factual Matters

Her Honour dealt with four further factual matters before proceeding to discuss the application of the insurance policy definition of flood to the circumstances of 3 and 4 February 2019.

Pile of Fill

There was a pile of fill on the vacant land to the west of the shopping centre. It was of sufficient height that most of it stood proud of floodwaters through the inundation of 3 and 4 February 2019. It was argued on behalf of the plaintiffs that this heap of fill provided a significant impediment to water flowing across the Gordon Creek floodplain and on to the shopping centre. However, Her Honour [at 165] rejected this, finding that it did not present any significant impediment to water flow from Gordon Creek and Gordon Creek diversion into the shopping centre.

Location of Gordon Creek Diversion and Concession as to Gordon Creek Diversion and Lake 3

Having accepted the defendants’ experts’ evidence as to the location of the Gordon Creek diversion, Dalton J noted [at 168] that Counsel for the plaintiffs accepted that water overflowing from the Gordon Creek diversion was water which fell within the scope of the exclusion clause. The concession extended to saying that Lake 3 was properly regarded as part of the natural watercourse of Gordon Creek as altered or modified. Her Honour concluded [at 170] it to be correct to act in accordance with the concession made.

Drain A2

A question arose [at 171] as to whether or not Drain A2 was a natural watercourse, although altered and modified.

Dalton J was of the view [at 173] that Drain A2 was to be regarded as a natural watercourse which had been altered and modified within the meaning of the exclusion clause. Her Honour considered it was quite comparable to the stormwater channel in Provincial Insurance Australia Pty Ltd v Consolidated Wood Products Pty Ltd & Ors (1991) 25 NSLR 541 finding that like the channel in that case, Drain A2 had been slightly modified so as to convey water more efficiently. In Provincial the channel was concreted and given brick walls. The modifications to Drain A2 were less than that. However, like the altered channel in Provincial, the modified part of Drain A2 performed the same function as it did before alteration.

Water Overflowing from the Normal Confines

Dalton J [at 174] observed that it was argued on behalf of the plaintiffs that Drain A2 could not be regarded as an altered or modified natural watercourse because it flowed through culverts. It was said that culverts were analogous to pipes, and that the judgment in LMT Surgical Pty Ltd stood for the proposition that if water flowed through pipes, the water could no longer be regarded as being from a modified or altered natural watercourse.

Her Honour said [at 175]:

‘It is abundantly clear that the decision in LMT does not purport to lay down any general rule as suggested by the plaintiffs. That case concerned pipes which were over 200 metres long and designed to allow water to drain from Milton into the Brisbane River. In a time of flood, the river rose so high that water surcharged through the pipes, ending up in Milton. In these circumstances Jackson J held that water did not overflow from the normal confines of the Brisbane River and therefore loss was not within the exclusion clause. The factual circumstance of Drain A2 passing through culverts under Racecourse Road and Stuart Drive is not analogous to this at all. The culverts simply allow water to pass along Drain A2 in much the same position as it always has. The culverts are more analogous to the brick and concrete channel constructed in Provincial. While the pipes in LMT were a functional replacement for an earlier natural drain into the Brisbane River, they did not follow the path of the natural watercourse, or arrive at the same destination as the prior natural watercourse. In any case, the pipes in LMT were a functional replacement, rather than a formalisation or alteration of the original natural watercourse: that contrasts with the situation here, and that in Provincial.’

Her Honour went on to say [at 176]:

‘In fact the water from Gordon Creek and Drain A3 passes through the unlettered culverts before it reaches the broad blue band which marks the start of the Gordon Creek diversion, yet it was conceded by the plaintiffs that all this area was a natural watercourse as altered or modified. I think the plaintiffs’ point about culverts in relation to Drain A2 can be seen to be opportunistic. In the same vein, the concession as to Gordon Creek and the Gordon Creek diversion being a natural watercourse, altered or modified, involved accepting much greater alterations and modifications as falling within the exclusion clause than were made to Drain A2.’

Plaintiff's Damage Arguments

Dalton J stated [at 178] that she found the plaintiffs’ argument that the insurer had never identified the particular damage to the plaintiffs’ property that the exclusion ‘operated on’ difficult to understand. In elaboration of this point it was said that there was no evidence led by the insurer to show when the damage claimed by the insured occurred – it may have occurred in the first hour after 6.30 pm on 3 February 2019, or it might not have occurred until as late as 12.20 am the next day. There was no evidence as to, say, whether or not all the damage to the centre had been done by the time water reached 30 centimetres height, or whether more damage was done between then and when waters reached their peak.

Her Honour found [at 180] that on the facts of the case, water flowed into the shopping centre during one event which started around 6:20pm on 3 February. Some time after 12:20am the next day, water ceased to rise in the centre, and the floodwaters began to subside. Damage to the centre resulted from the inundation. Dalton J noted that an insurance policy is a commercial contract and should be given a businesslike interpretation. Her Honour said that it would accordingly be unrealistic to interpret either the insuring clause, or exclusion clause 3(a), as requiring an inundating event such as this one to be broken down into stages, or that the insurer had to prove what parts of the physical damage suffered at the shopping centre could be attributed to various of those stages. Her Honour noted that no authority was suggested as supporting the plaintiffs’ approach in a case like this. Her Honour rejected this argument on the part of the plaintiffs.

Inundation of Normally Dry Land

Her Honour found [at 181] there was no doubt in this case that the shopping centre was built on normally dry land.

Plaintiff's Sources of Water Arguments

Her Honour observed that [at 182] the plaintiffs made submissions which amounted to identifying water which could not be characterised as ‘water overflowing from the normal confines of any natural watercourse or lake (whether or not altered or modified)’. They then contended that some of that water must have contributed to the inundation of the shopping centre.

Her Honour stated [at 182]:

‘…These arguments do not assist the plaintiffs. There are two major reasons. The first is that clause 3(a) does not operate by reference to the source of the water which causes an inundation. It excludes loss for damage which is occasioned by, or happens through, particular types of inundations. The second is the factual difficulty that the vast majority of water which inundated the shopping centre came from Gordon Creek, the diversion, and Drain A2, and this was water which was overflowing from the normal confines of natural watercourses, as modified or altered.’

Her Honour then have her reasons for each of these conclusions in turn.

Occasioned by or Happening Through

Dalton J observed [at 183] that the plaintiffs contended that the table drain, and the associated low-lying areas south of the shopping centre and north of the east-bound carriageway of Racecourse Road, were not part of a natural watercourse (altered or modified).

The plaintiffs’ counsel had conceded that water overflowing Gordon Creek and the diversion and then flowing overland and into the shopping centre was within clause 3(a) however, had argued that the defendants’ experts had not distinguished between water which came into the shopping centre from Gordon Creek and the Gordon Creek diversion as direct overland flow on the one hand, and on the other, water which had overflowed from these sources, but had then ‘either backed up in the northern table drain, or which was once within the northern table drain, or which is properly characterised as water overflowing the normal confines of the table drain, rather than overflowing the normal confines of a natural watercourse.’ [at 184].

Dalton J opined [at 190] that essentially the plaintiffs’ submission was that once water encountered the table drain as part of its overland flow from Gordon Creek or the Gordon Creek diversion, it should stop being regarded as water which was overflowing Gordon Creek or the diversion, and begin to be regarded as water which was overflowing the table drain. Her Honour concluded that having regard to:

- the size of the body of water moving across the floodplain compared to the relatively small amount of water in the table drain;

- the fact that the table drain was not flowing independently of the body of water moving across the flood plain; and

- the fact that the table drain was completely submerged by about 17:35hrs; she could not see that it was realistic to characterise the water which inundated the shopping centre as water overflowing the table drain.

Her Honour went on to note [at 191] that even if it were, the flaw in the argument remained that clause 3(a) was simply not concerned with identifying the source of inundating water. The damage excluded by clause 3(a) was ‘… damage occasioned by or happening through … water overflowing from the normal confines of any natural watercourse …’.

Having set out a series of cases [at 191 – 194] which confirmed that the phrase ‘occasioned by or happening through’ had a wide meaning and noting its application in cases concerning exclusions for ‘flood’, such as in Provincial, LMT Surgical and Wiesac, Dalton J concluded [at 196]:

‘Inundation damage to the shopping centre was occasioned by, or happened through, water escaping from Drain A2, Gordon Creek and the Gordon Creek diversion. That some water from those sources might at some time have lain in the table drain, or more likely, travelled across a flooded area beneath which was submerged the table drain, before flowing onto the shopping centre does not change that.’

Dalton J [at 196] could not see that damage to the shopping centre was ‘occasioned by, or happened through’, the small amount of surcharging water from grates in the car park, nor from local rainfall (some 12.8 centimetres of which had accumulated on the surface of the shopping centre car park).

The plaintiffs had submitted that water from the swale between the two carriageways of Racecourse Road rose up and flowed to the north, ultimately ending up in the shopping centre. Dalton J [at 200] could not see an evidentiary basis for that idea other than in the plaintiff’s expert’s views which she rejected. In the circumstances, Her Honour would not infer that water from the swale flowed over the east-bound carriageway of Racecourse Road to join with the table drain. Or that it did so in any significant amount. Or that any amount of it entered the shopping centre.

Wayne Tank Principle

Dalton J observed [at 201] that the case of Wayne Tank & Pump Co Ltd v Employers Liability Assurance Corporation Ltd [1974] 1 QB 57, is famous for the principle, ‘that if the loss is caused by two causes effectively operating at the same time and one is wholly expressly excluded from the policy, the policy does not pay’.

Her Honour noted [at 202] that in Sheehan v Lloyds Names Munich Re Syndicate Ltd [2017] FAC 1340, [81] Allsop J gave a modern re-statement of the applicable principles:

‘Thus, the Court should first seek to identify a single proximate cause of the loss or damage. If a conclusion is reached that there are instead multiple proximate causes, and one is an insured event but the other is not, then the insured will be able to recover. However, where there are two proximate causes and these are concurrent and interdependent, and where one is an insured event and one is an excluded event then as a matter of construction of the policy the insured will not be able to recover. The causes are inseparable, and as one is excluded under the policy recovery will not be possible.…’

After further setting out the evidence as to the source of the water and accepting that the figures generated by the defendants’ experts flood model were accurate enough (in summary demonstrating that Ross River inflows dominated the floodwater inputs at the site), Her Honour concluded [at 211]:

‘In these circumstances, I think the defendant has proved that there was a single proximate, effective or real, cause of the loss and damage caused by inundation of the shopping centre within the principles in Wayne Tank. That cause was water overflowing from the natural confines of Gordon Creek as altered or modified. That being so, clause 3(a) of the policy applied and the insurer’s liability to the plaintiffs was limited to $250,000. That amount has been paid.’

Conclusion

In LMT Surgical, Jackson J regarded the scope of the cover or exclusion of damage caused by flood to depend on the specific language deployed in the particular policy.

The subsequent decision of Davis J in Wiesac might be thought to provide an illustration of this, for as His Honour observed [at 105] there was only one word which was different in the flood exclusion under consideration in the case to that considered by Jackson J in LMT Surgical, which led to that case being distinguished on the facts.

In Landel, when determining the insured’s claim for indemnity under the policy in the face of an exclusion in identical terms to that considered in LMT Surgical, Dalton J said [at 175] that it was ‘….abundantly clear that the decision in LMT Surgical does not purport to lay down any general rule as suggested by the plaintiffs’, noting in any case that the pipes in LMT Surgical were a functional replacement, rather than a formalisation or alteration of the original natural watercourse, which contrasted with the situation in the case before Her Honour.

Accordingly, LMT Surgical seems likely to be seen as the high water mark in terms of the operation of flood exclusions utilising the ‘water overflowing’ nomenclature, with two subsequent Supreme Court of Queensland decisions having now distinguished it on its facts.

DISCLOSURE: The writer acted for the insurer in both Wiesac and Landel.

This article may provide CPD/CLE/CIP points through your relevant industry organisation.

The material contained in this publication is in the nature of general comment only, and neither purports nor is intended to be advice on any particular matter. No reader should act on the basis of any matter contained in this publication without considering, and if necessary, taking appropriate professional advice upon their own particular circumstances.